Author: Lisa Trapp

It’s easy to take our pollinator friends into consideration when the bright blooms of spring and fall are literally buzzing with activity, and when the lazy days of summer encourage nearby bees and butterflies to look for salt on sweaty arms. But we need to think of these helpful heroes in the winter too, creating a pollinator-friendly green space is a year-round endeavor.

Most bees and butterflies will be in a dormant period or state of “diapause” over the winter. Though in some instances this can occur in their adult form, typically they will be in this state as an egg, larva (caterpillar) or pupa. So what we do to our gardens in the spring, summer, and especially fall can greatly impact a successful re-emergence when temperatures start to rise and the flowers start to bloom.

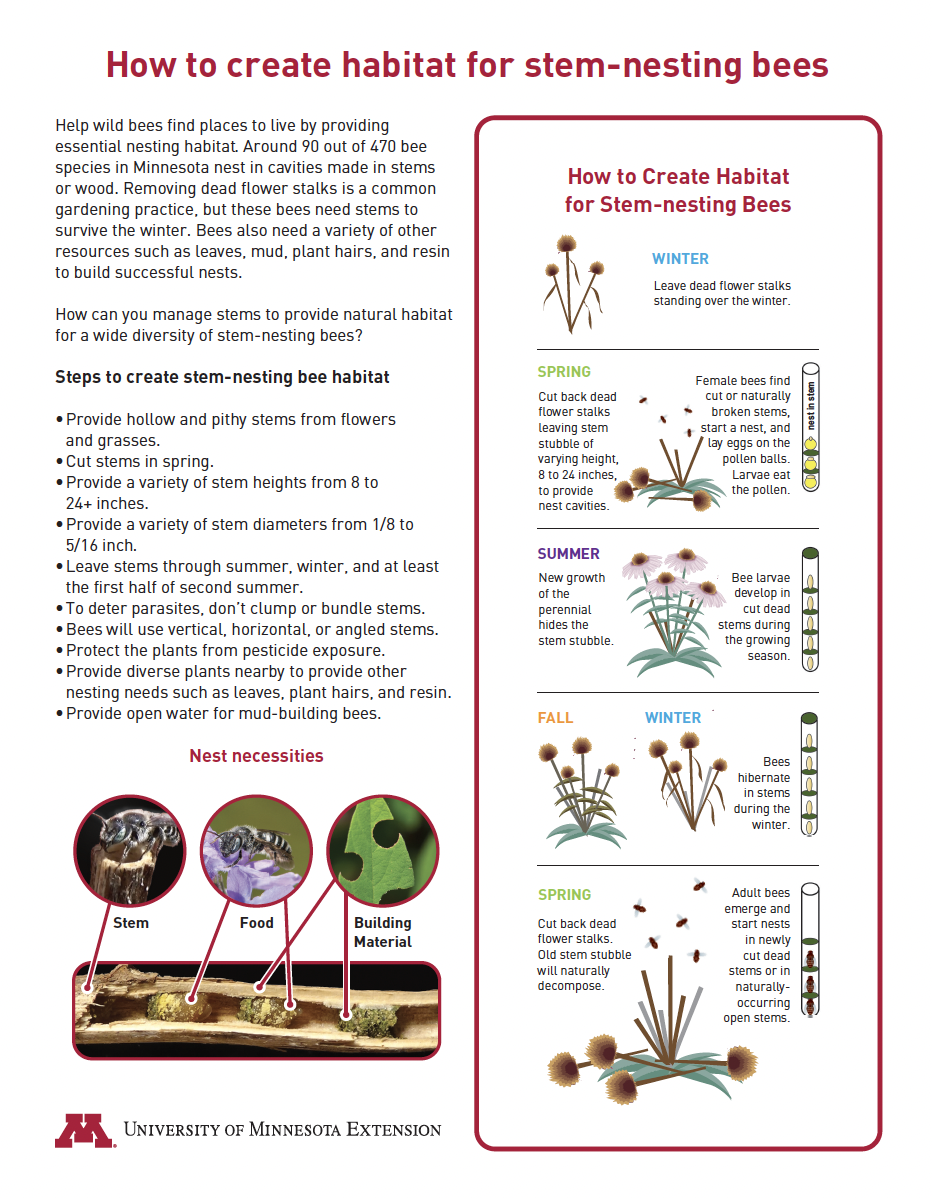

Undisturbed areas, like brush piles, logs, standing dead stems and bare ground are heavily utilized by overwintering insects. About 60 – 70% of our native bees are ground nesting and, depending on the species, can utilize anything from loose sandy soil to compact bare earth. As these insects spend much of their lives underground, what we put into the soil can have a huge impact on their development and survival. When possible, we recommend avoiding the use of pesticides, especially in areas of known nests, but avoiding harsh pesticides altogether is the most pollinator-friendly approach! The other 30 – 40% of native bees are mostly cavity nesters, choosing holes in wood, logs, and standing hollow plant stalks to overwinter. We encourage you to wait to do major garden cutbacks until it warms up in the spring, and leave plants, especially ones with hollow stems, upright in the garden. Keep in mind that you should manage these stalks on the bee’s schedule, which does not necessarily line up with traditional (read: pristine and tidy) landscape techniques!

https://beelab.umn.edu/create-nesting-habitat

Some of our favorite species of butterflies, including Fritillaries (Speyeria spp or Bolloria spp), over winter as camouflaged pupas beneath the fallen leaves. Leaving the leaves in place where they fall not only provides a natural compost but also allows these daytime pollinators to complete their life cycle. Though not pollinators, other eye-catching species such as luna moths (Actias luna) and woolly bears (Pyrrharctia isabella), also known as Isabella Tiger moths, also pupate in leaf cover. Early appearing species, like mourning cloaks (Nymphalis antiopa), question marks (Polygonia interrogationis), and commas (Polygonia spp.) are known to signal the coming spring. When temperatures are still cold they can be found tucked under peeling bark, and cracks in trees in their adult stage, waiting for warmer days. Since these guys are attracted to broken snags and decaying wood it is especially important to check firewood (if you use it) for any of these sleeping beauties!

When the garden is quiet it can be hard to tell what critters you might have passed below you in the soil, or laying dormant in the trees, but try to keep these guys in mind all year round. Out of sight shouldn’t be out of mind in this case! In the early spring before many of the plants have started to emerge, but temperatures are beginning to warm the soil, keep an eye out for small holes and tunnels which could be indicative of ground nesting bee homes. Wait to do any major cutbacks or remove leaves until temperatures are consistently above 50 degrees and make note of any species or homes you see throughout the year to better anticipate what might be hiding come winter. If you see any winter activity or unique species at the Low Line we would love to hear about it!

RESOURCES:

https://beelab.umn.edu/create-nesting-habitat

https://xerces.org/sites/default/files/publications/18-014.pdf

BEES An Identification and Native Plant Forage Guide, Heather Holm

https://butterfly-conservation.org/news-and-blog/where-do-butterflies-and-moths-go-in-winter

https://www.saveourmonarchs.org/blog/how-to-create-winter-habitat-for-butterflies

https://beelab.umn.edu/create-nesting-habitat

I am curious why Isabella Tiger Moths are not considered pollinators.